Nobel laureates are exceptional scientists but Geoffrey Hinton, the co-winner of this year’s Nobel Prize for Physics, is particularly so. Few laureates have expressed regret over the consequences of their own prize-winning work; none before they won the coveted prize.

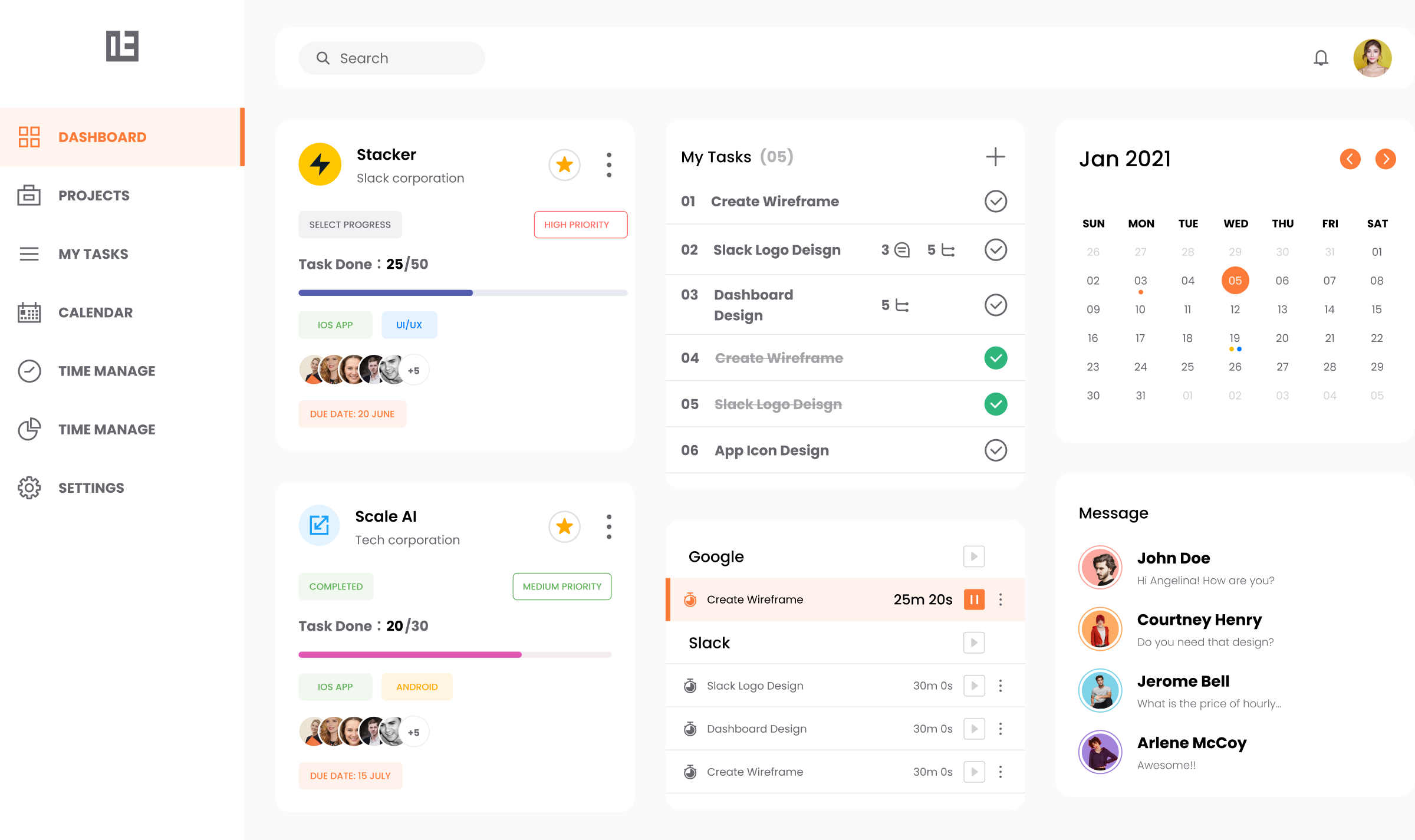

Explore this year’s Nobel winners and their achievements with this interactive guide

Hinton’s regrets

In May 2023, Hinton, a pioneer of deep learning, who has nurtured talented researchers in the computer science and Artificial Intelligence (AI) domain, quit his advisory role at Google. His reasons, according to The New York Times, were to be able to speak more freely about the “dangers” posed by AI. He said that a part of him “regrets his life’s work”. Developments in the ideas that he pioneered enable today’s learning machines to drive cars, write news reports, produce deepfakes, and take aim at professions that seem invulnerable to automatisation.

From being dormant for decades, neural networks, in his view, had suddenly become “a new and better form of intelligence”. He reckons that it would not be too much of a leap to expect AI systems to soon create their own “sub-goals” that prioritised their own expansion. Moreover, AI machines are able to almost instantly “teach” and transmit their entire knowledge to other connected machines — a feat that is slower and error-ridden in the animal brain. He expressed concern that AI could fall into the “wrong hands” and believes that Russian President Vladimir Putin would have little compunction in weaponising AI against Ukraine.

Whether or not experts saw AI as apocalyptic was a matter of being “optimistic or pessimistic,” he told MIT Technology Review, but there was near-consensus among those who understood these developments that AI presented a form of learning superior to that in people.

Ilya Sutskever, who completed his doctoral studies under Hinton, mirrored his mentor’s concerns. Sutskever as the Chief Scientist of OpenAI, the developer of ChatGPT, voted to fire Sam Altman as the CEO of the company last November. The coup failed, and ChatGPT lives in Microsoft’s stable. OpenAI’s foundational goal was to build “safe and responsible AI” and Sutskever, according to media reports, felt that the company was prioritising “profitability” over this original mission. Coincidentally, on the day that the Physics Nobel was announced, Hinton said that he was “particularly proud of the fact that one of my students (Sutskever) fired Sam Altman”.

Should Hinton’s assessment of the dangers of AI carry greater weight than, say, those of businessman Elon Musk, who has also spoken of AI as being a “risk to humanity”? Can a scientific authority always be trusted upon to do the right thing?

A lesson from history

In August 1939, Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard, his former colleague and friend and a fellow Jewish émigré, wrote one of history’s most consequential letters, to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. A year prior, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassman, working in Nazi Germany, had demonstrated nuclear fission, or the breaking up of uranium nuclei. With the spectre of World War II looming in Europe, Szilard and Einstein were concerned that a “large mass of uranium” could “liberate considerable quantities of energy” and create the most powerful bombs ever known, which could prove catastrophic.

The letter was essentially a plea to Roosevelt to fund and thoroughly investigate uranium and atomic bomb research. Einstein, a Nobel laureate already acknowledged as the world’s greatest scientist, brought considerable cachet with his words though his only connection to atomic research was in showing that mass and energy were equivalent. This letter, however, became the impetus for the Manhattan Project, a scientific and military effort by the U.S. to develop atomic bombs. While the scientists had hope that the U.S.’s efforts would prevent Germany from developing and deploying the most lethal weapon, it was finally the U.S. that ended up dropping atomic bombs on Japan, killing at least 2,00,000 people and inflicting inter-generational harm. Germany gave up on its bomb efforts almost mid-way through the war, while the U.S. went on to build and test more destructive hydrogen bombs that prompted Russia to up the stakes with even more powerful ones.

Before the bombs were dropped on Hiroshima, Szilard had appealed to the U.S. to control nuclear technology and prevent a nuclear arms race. The world knows how that has panned out. Today, nine countries together possess at least 12,000 nuclear warheads, with 90% of these distributed between Russia and the U.S. For all its purported potential for good, nuclear power barely accounts for 10% of the world’s electricity. Einstein deeply regretted his letter to Roosevelt and later said that it was the “one great mistake” of his life — his fears of German atomic armament proved unfounded and the country he had trusted to do better had instead charioteered humanity into the Atomic Age.

AI systems may not be plotting to incinerate humanity, but they are mushrooming at a time when globalisation has withered; and corporations, not countries, are poised to control technological advances and neural networks, and are also killing more jobs than creating new ones.

Hinton has called for the regulation of AI. If this leads to corporations monopolising AI, instead of facilitating an honest reckoning of its adverse consequences, it would be a redux of the Einsteinian mistake.

Published - October 22, 2024 12:54 am IST