When using a desktop computer at school or at home, what are the two most common devices that you use to provide inputs? The answer is quite easy: keyboard and mouse. Even though American inventor Douglas Engelbart is best remembered as the inventor of the mouse, he was much more than just that.

Born in 1925, Engelbart grew up on a farm near Portland, Oregon, U.S. As a boy in rural Oregon during the Great Depression, much of Engelbart’s childhood was spent roaming the woods and fiddling with things in the barn.

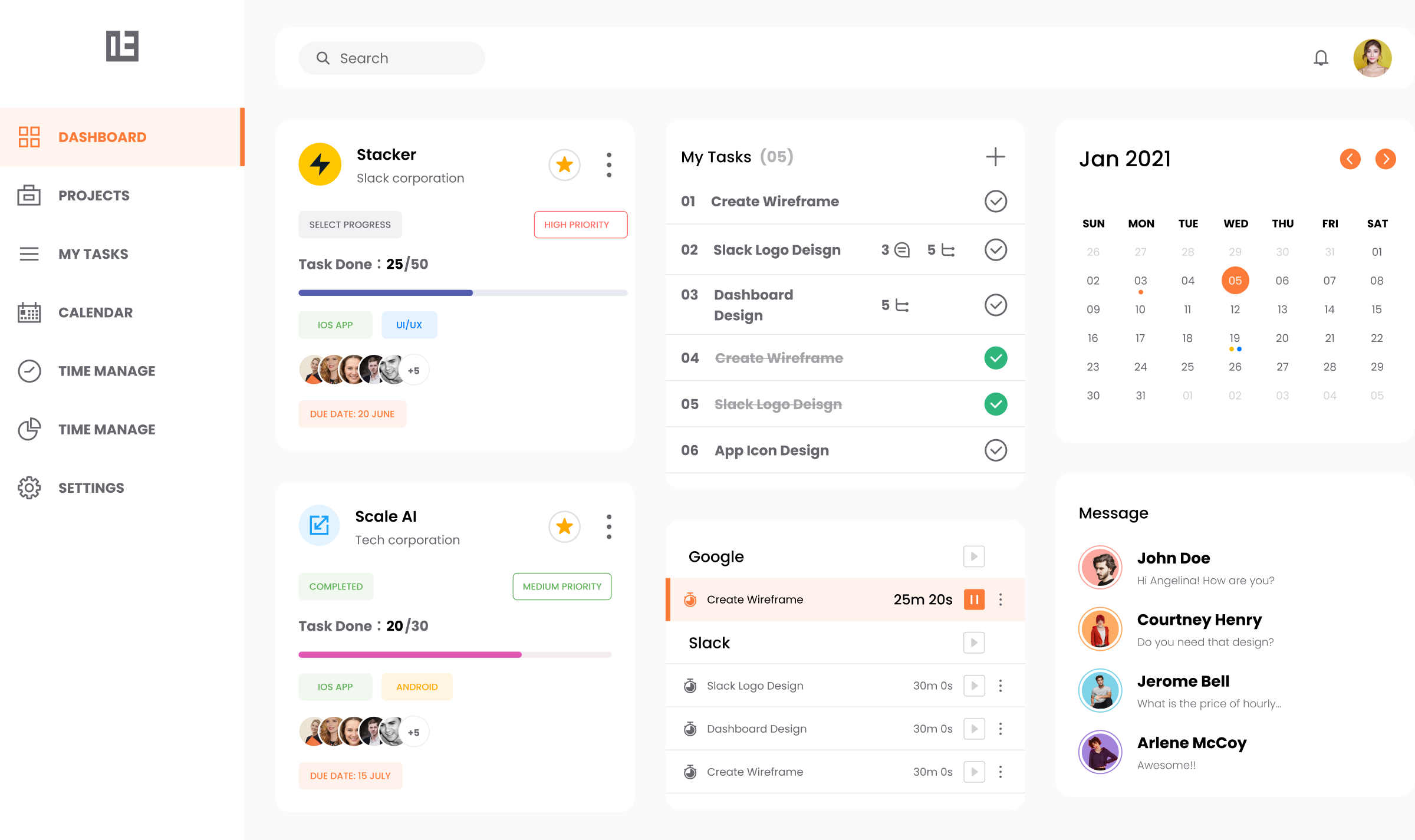

In this April 9, 1997 file photo, Doug Engelbart, inventor of the computer mouse and winner of the 1997 Lemelson-MIT prize, poses with the computer mouse he designed, in New York. | Photo Credit: AP

By 1942, Engelbart had finished his high school and took to studying electrical engineering at the Oregon State University. World War II forced a break in his studies as he spent two years of enlisted service as a radar technician for the U.S. Navy. Returning from service in the Philippines, he completed his bachelor’s degree in 1948 before heading to work for NACA Ames Laboratory, a forerunner of NASA, in Mountain View, California.

Finding a “complex problem”

Driving to work on a Monday morning in December 1950, just two days after getting engaged, it occurred to him that he was about to achieve both goals that Depression era kids grew up with. He was going to be happily married and he already had a nice steady job.

He realised that he didn’t have any specific goals. Or, as he put it in his own words, “it just seemed so strange to me that, at 25 going on 26, I had no more mature goals than that.” He decided to figure out his professional goals, realising along the way that “it’s a complex problem to pick a goal for your meaningful crusade.”

“Handle complexity and urgency”

And then, not long after, it hit him in a flash. “If in some way, you could contribute significantly to the way humans could handle complexity and urgency, that would be universally helpful.” In the early spring of 1951, Engelbart had what he wanted to go after.

Intuitively, it occurred to him that computers were the future. “If a computer could punch cards or print on paper, I just knew it could draw or write on a screen, so we could be interacting with the computer and actually do interactive work.“ He planned to devote himself to facilitate handling all that complexity.

Remember that all this was in the early 1950s, when the world had very few computers, and none like what we have everywhere these days. He went to University of California, Berkeley – one of the places that was building its own computer – and obtained his MS in 1953 and PhD in 1955. After staying on as an acting assistant professor for a year, he went to work at the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International).

Augmenting human intelligence

He earned plenty of patents in the years that followed, before publishing his seminal work in 1962, a paper titled “Augmenting Human Intellect: A Conceptual Framework.” At its core were his visionary ideas as he saw computers as a way to augment human intelligence. While many shrugged at his ideas and many more failed to grasp it completely, Engelbart went about delineating ways of viewing and manipulating information, which could then be shared over a network to enable collaborative work.

By 1967, Engelbart’s laboratory became the second site on the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET) – one of the main precursors to the internet. At the Fall Joint Computer Conference in San Francisco on December 9, 1968, Engelbart wowed the audience with an unprecedented demonstration that could have served as a gateway to some of his futuristic ideas.

Ideas beyond his time

While he did receive a standing ovation from the gathered awestruck audience at the end of the 100-minute presentation, few actually took to working on it right away – showing that most of Engelbart’s vision was a big leap for even some of the brightest minds of the day. He was a great proponent of collaboration, but his refusal to compromise as a colleague meant that he himself was unable to collaborate to further his ideas.

Image from Engelbart’s patent for a computer mouse. | Photo Credit: US3541541A patent

“I don’t know why we call it a mouse,” Engelbart had said during that demonstration when showing the tracking device that he had invented which helped move a small dot on the screen based on how he moved the mouse. A patent titled “X-Y position indicator for a display system” was applied for this device on June 21, 1967 and the patent was received on November 17, 1970. While it didn’t earn him much financially, the mouse was the one invention that earned him a lot of recognition.

Even though budget cuts at SRI meant that most of his research staff left for other institutions, Engelbart stayed on until 1977-78, when the lab was closed due to lack of funding. He joined Tymshare, which was acquired by McDonnell Douglas Corporation in 1984, and worked there till his laboratory was terminated in 1989. In that year, Engelbart founded the Bootstrap Institute, a research and consulting firm, with his daughter, focussing on R&D, speaking engagements, and workshops.

Delayed recognition

In the years that followed up until his death in 2013, and even after, Engelbart finally started getting much due recognition for all his brilliant innovations. He received over 40 awards, including the Turing Award and the Lemelson-MIT Prize, both in 1997.

When asked by Valerie Landau, an American designer, author, and educational technologist, as to how much of his vision had been achieved in 2006, Engelbart had answered, “About 2.8%.” He might have said that in jest, but there might be an iota of truth in it as well. American computer scientist Alan Kay probably summed it up best when he remarked “I don’t know what Silicon Valley will do when it runs out of Doug’s ideas.”

Engelbart’s demonstration on December 9, 1968 is often referred to as The Mother of All Demos as it turned out to be a landmark computer demonstration of developments, unmatched in quality both before and after it.

Backed by a team of engineers at SRI headquarters in Menlo Park, Engelbart waded his way through the demo at Brooks Hall – 25 miles away – during his demonstration of a system called NLS (oNLine System) – a working real-time collaborative computer system.

Engelbart introduced the world to a computer mouse, shared screen video conferencing, side along text and graphics display, “what you see is what you get” editing, windows, outlining, related help, version control and hypertext.

His ideas might not have caught on immediately, but they have certainly now changed the landscape of computer technology forever.

Published - November 17, 2024 12:25 am IST